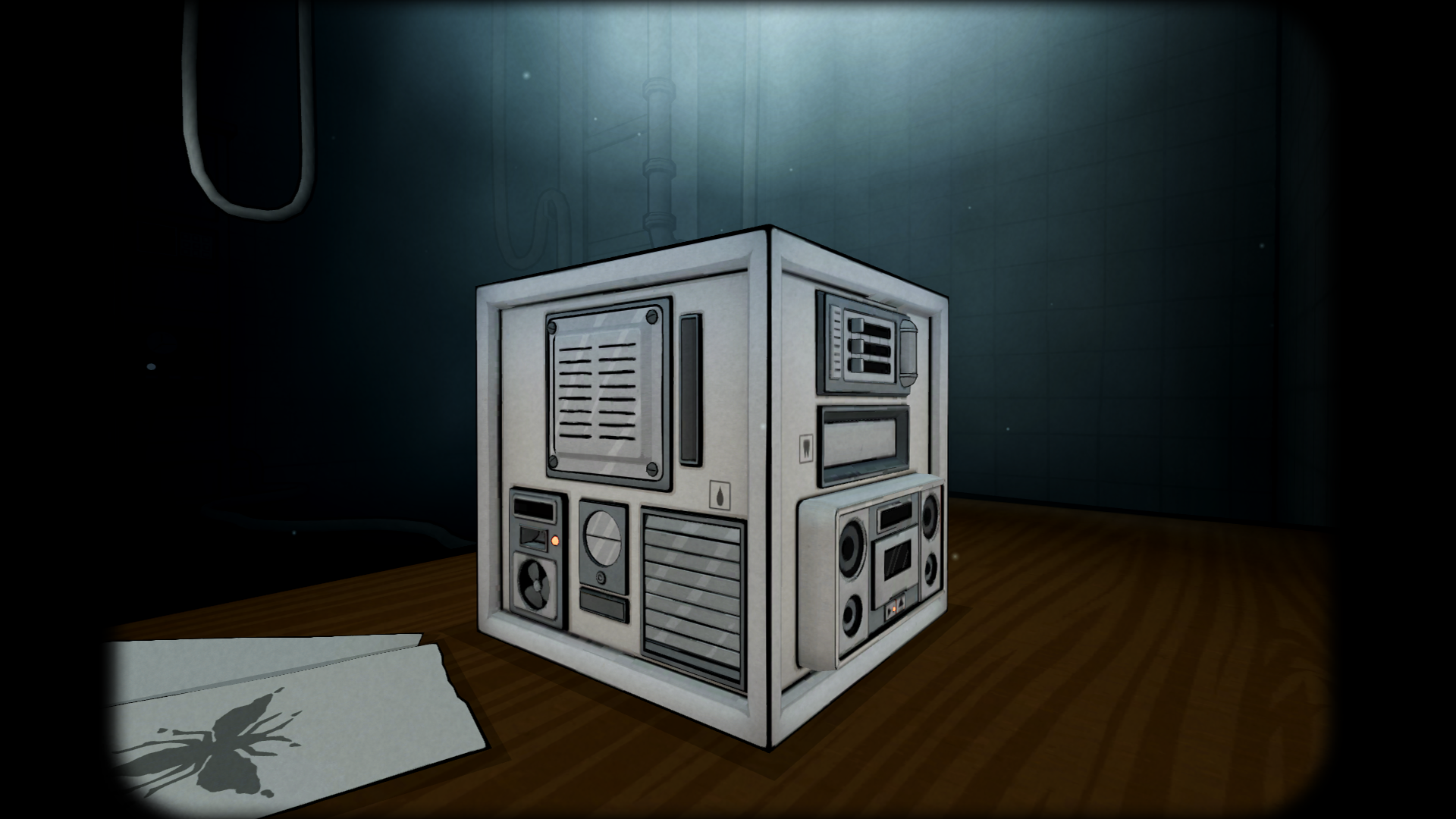

The Past Within’s fundamental use of two players means it’s a game someone cannot review alone, so we didn’t try to. Instead, Matt Wales and Victoria Kennedy paired up and here, collectively, in dialogue format, is what they think. Matt: Hi Victoria! What can you see? Victoria: Hi there! I am sitting at my desk, with my computer in front of me. And you? Matt: Funnily enough, I’m also at my computer - and if there’s one thing I’ve learned from our recent tangle with developer Rusty Lake’s new co-op puzzler, The Past Within, it’s that by combining our brains on the respective sides of our screens, we might just be able to puzzle our way to some final thoughts on the game. Now, I was already a big fan of the Rusty Lake games - and their free-to-play companion series Cube Escape - but this was your first Rusty Lake game, right? What did you know about the series before we played? Victoria: Yes, this was my first Rusty Lake game and until you mentioned The Past Within, the developer wasn’t on my radar at all. But I’m a puzzle fan, and after reading up on the studio’s previous titles, I was excited for some co-op fun. Matt: So, for those that don’t know, Rusty Lake specialises in casual, approachable – albeit gleefully sinister - puzzlers that riff on the classic room escape formula, all linked together with a surreal, loosely interconnected plot. That applies to all the studio’s games, but while the Cube Escape series keeps things short and sweet, the larger Rusty Lake games have become increasingly ambitious with each new entry. Rusty Lake: Roots, for instance, sees players ricocheting back and forth through time, visiting different members of a family at various points throughout their lives – giving the basic puzzling some wonderful emotional richness - while the recent White Door introduces an intriguing split-screen twist. The Past Within mightn’t shake up the puzzling fundamentals too much – it still plays out somewhere between a room escape game and point-and-click adventure – but it’s Rusty Lake’s first fully (and exclusively) co-op game, and one that comes with a compelling premise, asking players to solve a mystery across two separate, but concurrently unfolding timelines. Victoria: Yes! Players need to decide which timeline they’ll each occupy at the start of the game, and, for our playthrough, I was in the future while you were in the past - both of us playing on different devices. That means neither can see anything the other sees, but because progress requires players to interact with objects in their own timeline to find solutions to puzzles in the other, communication is essential at all times – and it’s vital for both players to form a mental picture of each other’s surroundings, not just what’s in front of them. Matt: And both set-ups are very different. My side of the experience – the past – will be immediately familiar to anyone that’s played a Rusty Lake or Cube Escape game before. I was dropped into the middle of an old-fashioned room, presented in hand-illustrated 2D, and could explore it by rotating at 90-degree intervals to scrutinise each wall, prodding and poking any suspicious corners for items and clues. Your side – the future - was almost the inverse of that though, right? Victoria: Yes, unlike you, I couldn’t explore the room around me at all, so I couldn’t really get a feel for where I was in the grand scheme of things. Instead, I had a cuboid device similar to a computer in front of me, rendered in full 3D, that I could rotate around to examine the various contraptions attached to its four sides. Most of its buttons were meaningless at first, but as we started to describe our surroundings and began piecing together how the items we could see might relate to those in the other’s half, the game - and the cube – began to open up. Matt: Yeah, so a very basic example might be that, by communicating what’s in front of us, we eventually both stumble across a near-identical pattern in our respective timelines – say, a labelled diagram tucked away in a drawer in the past, versus some unnumbered buttons hidden on the future machine – and by me relaying the correct order to press them, you might then uncover some new information I would need to apply on my side elsewhere. Things do get much more elaborate than that, of course – decrypting clues on one side to navigate a maze or play a macabre game of chess in the other – but that exchange of unseen information is a constant throughout. What was surprising though, was how different each half of the game felt – I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say both players get to try the two different styles of play as the story progresses - with the room section feeling a little more open, and more like a classic point-and-click adventure, while the box segments were much more claustrophobic and hands-on, very reminiscent of Fireproof Games’ wonderfully tactile The Room series. Certainly, I felt a lot more proactive in the room sequences, whereas I felt much more reliant on your guidance in my box section. Victoria: Yes, the box sections were almost the ‘control centre’ for the story beats. This is where we found instruction, and could act as a guide to the player who had free reign of the room they were in. I know when I was sat at my cube, I made a lot of notes and sketches based on your descriptions to ensure I had a clearer idea of what on earth was going on at your end. Turns out, I am not an artist! Matt: I was amazed when I saw all the notes you made afterward! But you’re right - when the roles flipped in the second half and it was your turn to have a whole room to explore, I found it much harder to visualise your timeline and ended up jotting a lot more down too. Victoria: I really appreciated that both players got to experience the different perspectives. When you were exploring your room during the first chapter, I did feel a little disappointed I couldn’t venture away from my cuboid ‘computer’ to poke around and investigate what was lurking in the corners. Not that this made the puzzles I was completing any less compelling, but the curious part of me was itching to step away from the table and find out what some of those noises were, and where the flickering lights were coming from. Matt: And I don’t think it’s possible to overstate just how much communication is required. Even though we tried to paint a picture of our surroundings for each other before we started puzzling, each player is still largely playing blind and absolutely reliant on the other, and that meant we didn’t stop talking at all for the four or so hours it took to wrap things up! Victoria: I needed a large pint of water to refresh my throat after we finished because we really were non-stop talking for the entire game! Matt: I’d probably go as far as to say that it’s the communication element that’s the real challenge in The Past Within – the puzzles themselves are all straightforward enough to keep things pacey – but with both players completely blind to the other half of the game, it really is vital to communicate clearly and precisely, and it turns out that’s much harder, and more mentally strenuous, than it sounds! And I think that helps turn what’s a relatively casual puzzler at heart into something with its own very distinctive feel. Victoria: I have to agree with you about the puzzles; once I’d settled into what the game was all about, the next steps were fairly logical when you stripped them back and ignored the (literal) corpse in the room. And, at no point did I feel my part in the split timeline was taking a backseat to yours, it was well-balanced throughout. Matt: Yes, and I’d say it’s definitely accessible enough to be picked up and played by any puzzle lover, regardless of their gaming experience, and I love the fact that being entirely built around blind information makes The Past Within such a great equaliser. It’s really very difficult for either person to railroad the experience and completely take over. Victoria: Just be warned, some of the things you’ll have to describe to each other are pretty off the wall! Matt: Yeah, there aren’t many times I’ve had to tell someone, “I’m just sliding it into the corpse now!” over the phone. Victoria: I did appreciate the little reminders that something macabre was going on. Sometimes, I was so focused on the puzzle at hand, the bigger picture of the unfolding story got a little lost - and then suddenly there it was in my face again, and hearing you describe your adventures with the corpse was equal parts funny and horrifying. Matt: I did want to ask what you made of the overall vibe! The series is pretty distinctive in its weirdness - part gruesome silliness, part maudlin horror, with the occasional dollop of existential dread - and I wondered what a newcomer made of it all. Victoria: I really enjoyed the vibe - there were definitely sinister moments, but never in an overbearing ‘I won’t be able to sleep at night’ kind of way. But perhaps I would have found it creepier if I’d been experiencing this all on my own. Our upbeat chatter did keep the mood lighter than I presume you’ve found in your previous forays with the Rusty Lake games. Matt: Yeah, I think if there was one real disappointment for me, it was that the constant need to communicate and chatter did sort of undermine the lovely creepiness that’s always been the hallmark of the Rusty Lake games. But now we’ve puzzled our way through all that, I guess it’s time to combine heads and come to a conclusion – is The Past Within deserving of a coveted Eurogamer badge? Victoria: Overall, I enjoyed our time with the game. I’d say its overarching narrative was compelling, the gameplay mechanics were easy to grasp, it didn’t overstay its welcome, and visually it all looked very nice. And I particularly liked the focus on teamwork between both timelines. While I’ve played time-hopping games before, this one really stood out for its unique approach – and definitely made me want to try out more games by Rusty Lake. Matt: Yes, and obviously I was coming to the whole thing from a different perspective, having already been a big fan of the Rusty Lake series – so the chances I was going to like The Past Within were always pretty strong. But even viewed in isolation, I think it’s a fascinating co-op experience - certainly quite unlike anything I’ve played before. Just that absolute focus on communication and teamwork introduced a kind of challenge I genuinely wasn’t expecting, but found enormously rewarding all the same. Honestly, I’d be inclined to speak highly of The Past Within if that was it, but as well as being wonderfully accessible, it’s also cheap as chips (it’ll cost between £2.50 and £5 on release, depending on your chosen platform), and there’s even a second mode which features slightly remixed puzzles so both players can have a go in the other timeline without just marching through the same steps all over again. Ultimately, as long as you understand its puzzles are pitched toward a more casual audience and that it’s a relatively short game – albeit one that feels just the right length given its mental demands - I think it’s an easy sell. But if we’re going to do this the proper Past Within way, we’ll both need to commit to a countdown and press the appropriate buttons at the same time. So, 3…2…1… Victoria: Recommended. Matt: Recommended.