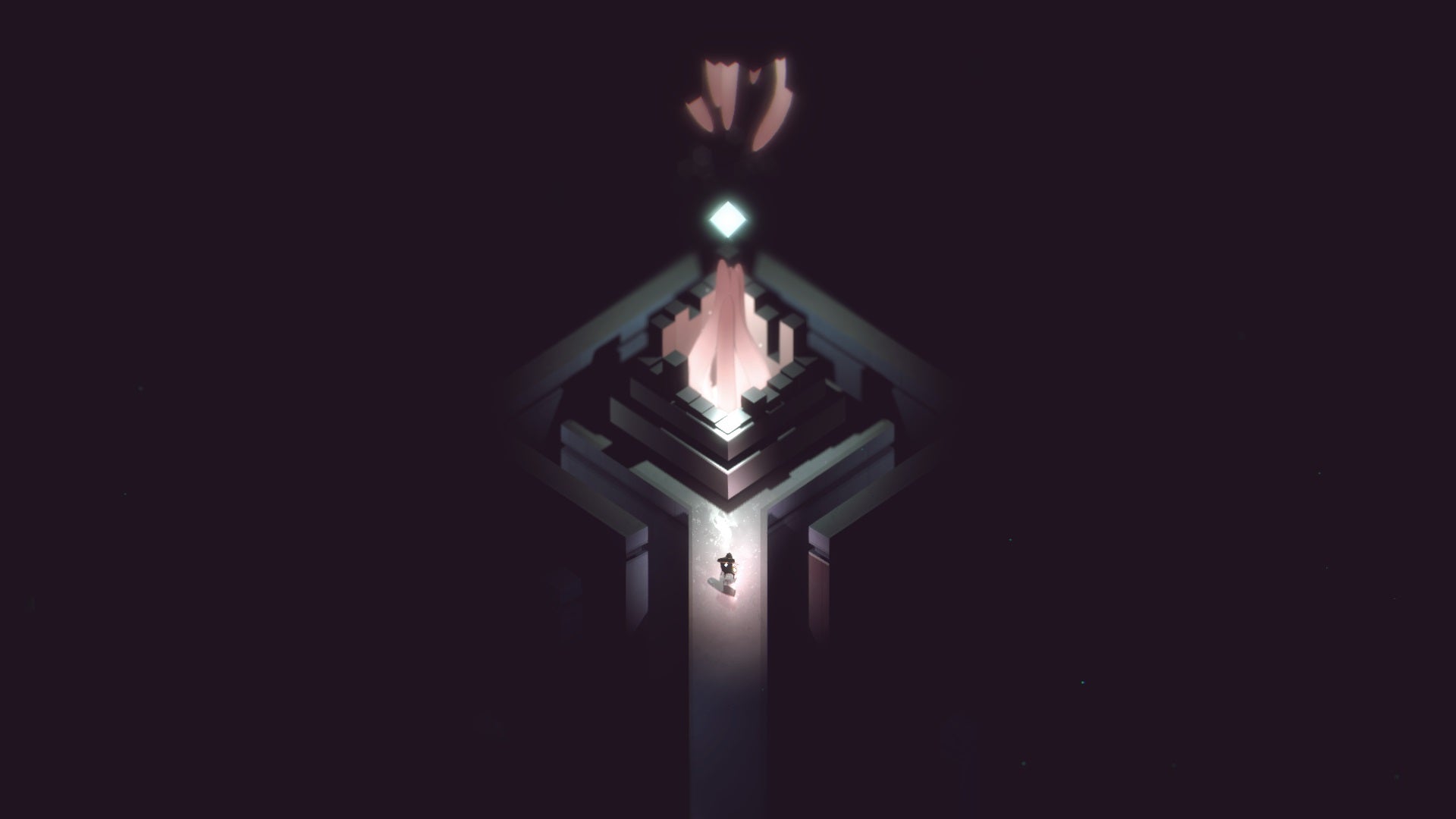

We hope you enjoy this piece from Kaan as he picks over one of the most wilful Soulslikes out there. This piece contains spoilers for the ending of Below. Why do we play Soulslike games, those brutally difficult games based on From Software’s now-iconic formula? Is it the frustration of falling off of a tricky platform in Blighttown? Is it the satisfaction of perfectly strafing and executing a successful backstab? Is it the frantic rush to reunite with your latest corpse in an effort not to waste the last half hour of your life? Or is it that feeling of accomplishment? That feeling of dying and dying and dying, again and again and again. The feeling of being one hit away from the words, “YOU DIED”, barely dodging a bosses’ attack and finally ending it with one last swing. Exhale. Difficult games are built on this feeling. On this loop of agony and elation, frustration and triumph. Beating tough games can become a form of therapy, as it is in Celeste. When Madeline’s anxiety has her break down, you’ll be asking yourself the same questions: “Can I even do this? Am I good enough?” Suddenly beating the game becomes about proving to yourself that you can do this, that you are strong enough, that you’re capable of climbing that mountain. But Capy’s 2018 roguelike, Below, doesn’t inspire the same feeling, despite its brutal difficulty. The game follows wanderers who sail to an isolated island and descend into the depths of it. Each death leads to another wanderer landing on the ominous shores, attracted to something below. On the surface, it should fit snugly next to games like Dark Souls. Below includes all the most gruelling parts of Soulslike games - one-hit kill traps, relentless enemies, losing resources upon death and having to recover them from your corpse. This is mixed with some survival game elements like hunger and thirst metres that act as a ticking timer, counting down to your next inevitable death. While Below includes all the classic chunks of a Soulslike, the sense of elation and the feeling of victory don’t exist here. Each victory is met with a reminder that something worse waits below. Sure, I came out of one particularly tough encounter alive, but the resources I lost mean I’ll be ill prepared to survive the next fight. Below’s roguelike nature also adds to this never-ending sense of dread as you repeat levels that have killed you. You know what comes next and you know it can kill you again. Below’s design is overwhelming as you endlessly crawl through it’s ever-changing world: it didn’t inspire anything traditionally good in me, sweating, frustrated, screaming into my brain. But I still found myself turning up the volume, turning down the lights and returning to its darkness anyway. Half-way through your descent, the game introduces ghoulish humanoid enemies who frantically crawl on all fours. I got the feeling that if my wanderer survived long enough on the island, trapped with the game’s maddening systems, they wouldn’t look too dissimilar to these unfortunate fiends. If Below’s value doesn’t lie in its enjoyment, why couldn’t I stop playing? I suspect the answer to that question can be found in the game’s wild ending. After surviving a seemingly insurmountable series of obstacles, the wanderer unleashes an indescribable cosmic horror - a darkness that engulfs the entire island, then the entire planet, then the entire universe. It’s a devilish twist with, again, no joy or triumph to be found. The game has you battle with starvation, fighting for your life, just so you can feed a darkness that corrupts the entire world. Maybe it’s a metaphor for capitalism as the island churns through an endless supply of workers who have no choice but to engage with nihilistic systems for fear of death. If this is the case, it’s disturbing. It makes you feel dirty, it points out the inequality that comes with purely playing the game in the first place. With an ending - and a game - that’s so open to interpretation, it’s difficult to stamp a proper meaning to it. I can mutate Below’s disparate parts to fit any conclusion I come to since, like From Software’s games, Below relishes in withholding information. But there is something here about being attracted to darkness. Not the lack of light, but the violence and struggle we’ve grappled with since the beginning of time. It’s just that unlike most Soulslike games, there’s no glory or victory here. Violence and death are bad and Below doesn’t change that. This attraction to darkness, to violence, manifests itself in real ways in Below. The game’s Norse imagery - the Icelandic island, the Viking longships, the armour - plays into this idea of endless violence as it does in Seamus Heaney’s book, North. It’s something that’s followed us throughout time, something that we can’t escape. The violence in the game is as cyclical in this game as it is in history as one wanderer dies only to be replaced by another soon-to-be victim. The vikings were defined by death and so are we. You die and you die and you die. The death counter hits triple digits in Celeste. You almost smash your third controller in Dark Souls. This cycle is taken to the extreme after the cataclysmic ending as the game simply returns to the very first scene: a lone wanderer sails to an isolated island. The game starts again. Death isn’t followed by credits in real life and that’s the case here too. Below’s addition of roguelike elements to the Souls formula should be more widely explored. It takes a genre all about death and repetition and makes it overt, drawing our attention to this never-ending cycle. So, to return to my earlier question of why I couldn’t stop playing? I reckon it’s for the same reasons the wanderers keep turning up to an island filled with death. Or maybe it’s more pertinently described by the first track of Below’s OST, Moth to a Flame. We’re attracted to that darkness, being pulled below. Whether it’s the violence we glorify and enjoy in film and games, or the death we voyeuristically consume on the news and online. Below isn’t a game for everyone, or for most people. Since launch, the developers have added an Explore Mode that makes some of the game’s merciless systems more manageable - if you want to soak up Below’s lone, oppressive world without the overwhelming difficulty. But just like Dark Souls and Celeste, Below is a game that says something through difficulty.