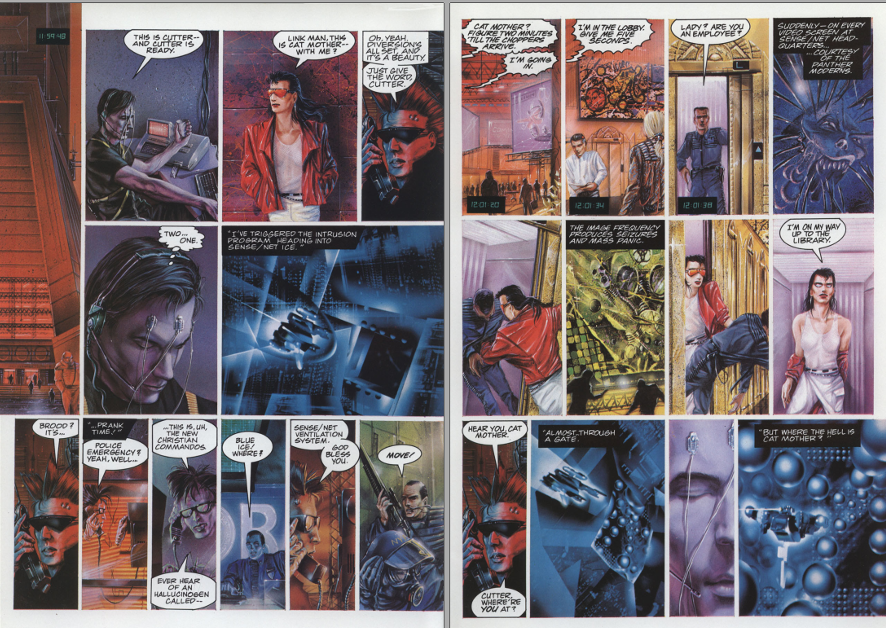

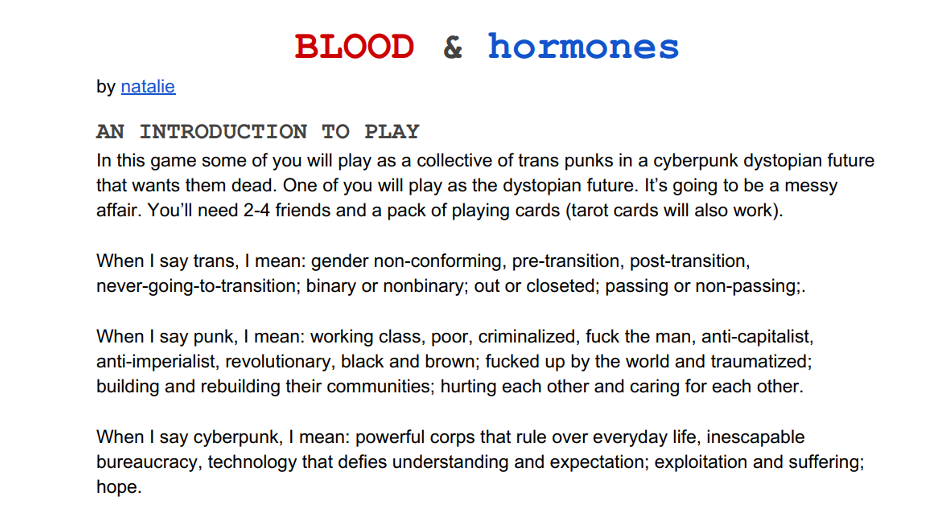

And while we have you here, if you’ve been eagerly awaiting a restock of Eurogamer’s Pride t-shirts, we’re happy to report that more - in two ravishing variants - are now available for purchase. All profits will be split between LGBTQIA+ charities Mermaids and Mind Out. I’d like to begin this piece with a coming out of sorts. “What better time to come out than Pride Month?”, I hear you say. “There’s no judgement here.” “This is a place of love and support!” But, I fear there is no pride to be taken in this admission. For you see, dear reader, I am someone who unironically quite enjoyed Cyberpunk 2077. I certainly didn’t think it was the Second Coming / pizza-that’s-also-ice-cream-that-gives-you-orgasms-while-doing-your-taxes epochal experience it was hyped to be, but, nor did I think it was absolutely execrable. It was schlocky and fun and a surprisingly accurate reflection of the tone (and jank) of its table-top RPG source material. But, when I compare my experience of playing Cyberpunk 2077 to my experiences of playing Cyberpunk 2020 and Cyberpunk Red (the TTRPGs that provide the world-building and mechanical underpinnings for CD Projekt Red’s adaptation) it did miss the mark in one area rather significant area: queerness. Notwithstanding the rather gorgeous Judy – ‘feminine’ V underwater romance sequence, and the nuanced characterization given to Claire, a trans woman with a complicated past who serves as the Afterlife’s charismatic bar-tender and oversees the game’s street racing circuit, queerness felt like something of an afterthought. I’m far from alone in feeling this, and some incredible pieces have been written taking the game to task for this that I strongly advise you to check out, but they’ve tended to focus on the way queer characters and queer identity are handled in-game. In this piece I want to go after something a little different. In the spirit of Pride month, and the liberationary, transgressive, and transformative traditions it honours, I want to explore how cyberpunk as a genre, and gaming as a medium, could facilitate a queer interrogation of the nature of identity itself. At the heart of social, cultural, and political life as it is lived in the contemporary West is the inexhaustibly vexed notion of identity. The nature, properties, and origins of the self is a philosophical chestnut as old as Plato. At its best, the concept of identity, or, more particularly, the categories through which it is structured and made legible to others, can offer a valuable rallying-point for shared understanding, community solidarity, and co-ordinated political action. At its worst, however, identity can become a strait-jacket, used to confine or exclude those who wish to live or love outside the boundaries of the dominant culture. However, while Pride undoubtedly partakes of the positive vision of ‘identity’ outlined above, and is the better for it, queerness, as it has been theorized in academic settings, and, far more importantly, as it has been defiantly manifested in the lives and activism of generations of queer people, tends to position itself against the grain of this sort of identitarian thinking. In one particularly influential formulation, the literary scholar and historian of sexuality David Halperin asserts that “Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers. It is an identity without an essence. ‘Queer’ then, demarcates not a positivity but a positionality vis-à-vis the normative… [Queer] describes a horizon of possibility whose precise extent and heterogeneous scope cannot in principle be delimited in advance.” In contrast to essentialist models of identity, which claim that a person’s character is fixed, stable, and determined by some pre-existing essence (often conceived in terms of notionally ’natural’ categories such as race or sex), this mode of queerness queries such categories, destabilizing the ground upon which they rest. It does so not because queerness is a ‘choice’ that could, under sufficient duress, be reversed (Spoiler Alert: it is not), or because queerness is a ‘pose’ that is less authentic than its more ’natural’ counterparts, but because, as Oscar Wilde put it, and queerness seeks to expose, “being natural” is itself “simply a pose”, and probably the “most irritating” (and dangerous) pose there is. So how does cyberpunk fit in to all this? As more than a few people have noted across the years, cyberpunk is a genre that resonates strongly with these conceptual elements of queerness. While the first wave of cyberpunk fiction did not always do a stellar job in terms of queer representation, staging scenes of same-sex intimacy for the titillation of a presumed cis-hetero male readership, or fetishizing trans people as emblems of body-modification culture run rampant, the questions it raised about consciousness and embodiment possessed a palpable queer charge. In one of the most striking sequences in William Gibson’s endlessly influential 1984 debut novel Neuromancer, the terminally alienated hacker-protagonist, Case, jacks-in to the sensorium of mirror-shaded street samurai, Molly Millions, as part of a heist on a corporate data stronghold. Immersed in Molly’s ‘SimStim’ feed (and thus experiencing her sensory data, physiological responses, and embodied affects in real-time), Case is overcome with a vertiginous sense of connection with Molly; the first stirrings of an empathy that will eventually impel him to help a rogue AI to pursue the development of its diffuse, networked consciousness. As a non-binary trans person, encountering this sequence for the first time stopped me dead in my tracks. The ‘gender feelings’ (trans Spidey-sense for when normative paradigms of sex and gender are being transgressed, or trans experience is being evoked) were strong with this one. Beyond offering a novel way to approach staging and narrating a heist, it has always struck me as a sequence haunted by a sort of spectral gender euphoria: a dream of experiencing, in an instant, as if by magic, another mode of embodiment that might fit better, or even just differently, from one’s own; another instantiation of consciousness and the flesh it both permeates and emerges from as it makes itself legible to the world. While Case’s desire to transcend ‘meatspace’ – Gibson’s term for fleshly embodiment and the mundane, non-virtual world that accompanies it – has been rightly critiqued for endorsing a rationalist fantasy of the self-sufficient masculine intellect overcoming the limitations and distractions of the (traditionally feminine coded) body, moments such as these complicate that dynamic. Instead of sponsoring a masculinist vision of consciousness surpassing the perceived limitations of corporeality through technological mastery, passages such as this suggest the ways in which such technology could render the ‘self’ more porous, complicating, rather than erasing its ties to the body. (In what feels like a suitably cyberpunk endorsement, I had this intuition apparently confirmed for me on Twitter when Gibson himself liked and retweeted some thoughts I shared on the topic. So, if nothing else, I can basically die happy, crushed under this clanging name-drop…) As this example suggests, central to cyberpunk’s challenge to the sorts of monolithic, restrictive, and exclusionary model of identity outlined above is, of course, the figure of the Cyborg. The Cyborg, as conceived most influentially by queer feminist philosopher Donna Haraway, constitutes a stark, and deeply queer, rebuff to essentialism and the narrow politics of identity with which it is bound up. For Haraway, the Cyborg – a fusion of animal and machine, such as the protagonist of Alice Bradley Sheldon’s The Girl Who Was Plugged In, or you reading this on your smartphone – eschews all myths of ’essence’ or ’naturalness’. It is deeply impatient of narratives of lost innocence and maintains a thoroughly disenchanted awareness of its own status as a social and technological construct. Straddling the blurred boundaries between ‘animal’ and ‘human’, ‘human’ and ‘machine’, and ‘physical’ and ’non-physical’, in Haraway’s evocative phrase, the ‘Cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and does not dream of returning to dust.’ To those who would point at it and say ‘you are unnatural’, the Cyborg replies ‘so what?’ and proceeds to reconfigure the colour of its fibre-optic undercut while hot-swapping its genitals to better suit the vibe. Crucially, though, the Cyborg is also under no illusions about the position it occupies within the exploitative networks of globalist corporatocracy and surveillance capitalism that facilitate its trans-human existence. Instead, the Cyborg knowingly leverages these limited resources in the furtherance of provisional, fluid, and non-exclusionary modes of solidarity and community. Eschewing the illusory ‘wholeness’ or ‘innocence’ of an identity uncontaminated by oppression and inequality, Haraway’s Cyborg works with what it has to build a more equal and inclusive future in which ‘freedom’ and ‘justice’ are evolving collaborative practices, rather than static end-points. Unsurprisingly, few areas of human cultural activity are as closely enmeshed with the figure of the Cyborg as gaming. Every time we pick up a controller, don a VR headset, or manipulate a digital avatar, we are functioning as a form of Cyborg life. As such, my pitch to you, dear reader, is that we, as gamers, and particularly queer gamers, are ideally placed to inhabit the space of plurality, fluidity, and disillusioned vigilance Haraway envisages as the antithesis of essentialist identity, and, what’s more, that Cyberpunk games can and should be offering us that experience. In making this assertion, I am calling for a move through and beyond ‘representation’ – the presence in media of members of marginalized groups who can serve as spokes-people and role-models for those groups – to a more abstract, structural, but, perhaps, more conceptually thoroughgoing engagement with queerness. In a media environment in which the lives, experiences, and aspirations of queer people continue to be grossly misrepresented, often for profit and to serve strategic political ends, I am never going to complain about better representation, especially where it results in queer writers, developers, and performers being given the opportunity to make a living doing what they love. To be absolutely, unequivocally clear, LGBTQIA+ people need and deserve better representation in and from the gaming industry. Right now. This second. But, as I have tried to argue here, in its interactivity, its networked connectivity, and its inherently trans-human dimensions, gaming also provides us with a potentially liberating opportunity to ask more daring and, above all, queerer questions about identity. What does it mean to think of subjectivity away from rationalist, bourgeois, or neo-liberal individualism? What might it look like and feel like to inhabit an identity without an essence? How might a game’s mechanics be structured so as to let us think, act, and play, not as an omnicompetent, iconoclastic bad-ass, ’transcending’ the limitations of ‘meatspace’, but as a fluid, vulnerable collective, enmeshed with a variety of bodies in complex and evolving ways? Features like the network-building and character-swapping at the heart of Watchdogs Legion, or plot structures like the fight for survival and gender-affirming resources that drive the fluid cast of trans characters in a TTRPG like BLOOD & hormones, offer potential avenues that future cyberpunk games might pursue further in answering these questions, (even as they oblige us to confront the paradoxical ways in which a triple-A game like Watchdogs Legion harvests player data for corporate ends.) In Song of Myself, Walt Whitman, who, though he lived almost a century before the emergence of cyberpunk, knew a thing or two about ‘bodies electric’, offers a famous celebration of inconsistency and multiplicity: “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself / (I am large, I contain multitudes)”. As a person whose felt gender, gender expression, and sexual preferences can shift multiple times in the space of a day, the idea that I am never more ‘authentically’ queer than when I am contradicting myself is bracing and empowering. At the same time, as we increasingly come to inhabit and surpass the corporatized, crisis capitalist nightmare envisaged by so many foundational cyberpunk texts, the imperative to be under no illusions about the place gaming as an industry occupies within structures of socio-economic domination, neo-colonialism, and the exploitation of natural resources seems central to the spirit of protest and resistance that has animated Pride from its start. My dream, this Pride Month, is to pick up a cyberpunk game just as contradictory, large, and multitudinous as I am, and to emerge from it feeling affirmed, galvanized, and, dare I say it, proud of the fluid, politically-engaged identity I share with so many of you, my fellow Cyborgs.