It does blind us to the gems the studio crafted before their cultural juggernaut came along though. While many are clamouring for From Software to revive its mech combat series Armoured Core, I’m pining for the team to bring back a criminally overlooked and largely forgotten horror game for the Playstation 2: Kuon.

Which is fitting since Kuon is a game all about resurrection. The terrible curse that has befallen Fujiwara Manor, during the Heian era of Japan (about a thousand years ago), centres around an attempt to revive the dead through nine cycles where, in each one, the undead must merge with increasingly larger hosts to stay alive. Like the approach to immortality taken in From Software’s more recent games, this process is horrific. An affront to nature itself that decays the world around it. A disease that stems from the rich and powerful and works its way down. The servants, we learn, were among the last to be effected.

Players explore the manor in multiple roles, with two campaigns and a third unlocked after their completion. Their overlapping stories interweave in a manner not unlike Resident Evil 2’s lauded campaigns. You start as Utsuki, a young woman trying to find her father on behalf of her sickly sister. Her father is an onmyōji, which the English translation simplifies as an exorcist. They are somewhat akin to an exorcist in this game but the reduction does obscure their real-world history as astrologers, diviners, calendars, and more, all practices present throughout Kuon in addition to occult spells. Their practice stemmed from the Yin and Yang Five Phases philosophy, and allowed them to serve as advisors throughout Japanese history. As jobs go, it was pretty cushy for the time. The philosophy aims to define all phenomena as according to five elements/seasons, which encompass the year’s cycle, corresponding to Yin and Yang. In the game this philosophy governs the natural order and the dark ritual at the heart of the story offers additional phases, disrupting the balance in attempt to extend life itself. The two campaigns are defined in the game as the Yin and Yang phases, with each narratively embodying dual natures and phases of the philosophy. Birth/death, growth/decay, masculine/feminine. All things in balance. A third, unlockable campaign, the titular Kuon phase, which roughly means eternity, reveals all and concludes the ritual and story.

This rooting in real beliefs and folklore gives Kuon a richness not easily replicated. Its ideas are so intricately woven, lending its supernatural story a coherence players can ground themselves in. Fans of Demon’s Souls and onward will find much to appreciate in Kuon’s dense, overlapping mythology and Sekiro players will even recognise elements like monstrous apes and overgrown centipedes. The creature design in general is some of the studio’s best, tapping into a grotesque body horror that doesn’t just rely on oodles of pulpy gore. Spirits crawling out of open wounds (another familiar sight for Sekiro fans) makes crawling out of a well and through a telly look quaint.

Its specific notion of the supernatural isn’t just for the story. The player must heal through meditation, only possible when enemies aren’t around, and saving involves a purification ritual, requiring a paper vessel to carry negative energy downstream. Your main defence against the supernatural are paper cards. These allow you to cast spells and summon all manner of entities like divine wolves or trapdoors to hell itself. It’s probably inspired by onmyōji myth of summoning shikigami, a spirit that can possess or take the form of animals and even people. In Kuon these summons are a precursor to the spirit ashes that have helped Elden Ring stand out, providing you with temporary allies.

Despite these imaginative player tools, Kuon was maligned at the time by critics for its retreading of survival horror tropes and mechanics. Combat is the weakest component, I can’t deny it. It’s generally too simplistic to be a draw in of itself but still, there’s potential here well worth a revisit, as proven by the appearance of a similar system in Elden Ring. With From Software’s current chops, it’s not hard to imagine the imaginative underlying system getting a deep makeover in a sequel.

It didn’t help that Kuon released in 2004 with the revolutionary Resident Evil 4 right around the corner. In 2022 though, after almost two decades of Resi 4’s inescapable influence, Kuon feels fresh. It puts its visuals and atmosphere first and foremost. Enemy encounters are infrequent, as are puzzles. You’re practically forced to slow walk through all of its blood soaked halls and hallowed grounds as running can summon enemies, enforcing a pace that games seldom make time for.

Gently paced as the game is moment to moment, the story has a real momentum to it and brings its slow burning story to a fiery crescendo. Each campaign quickens in pace, with the first being the longest and the last completable in a single hour. It’s a drive that compliments a genuinely compelling mystery, with each new perspective reframing everything before it and gently leading us from what appears to be a straightforward horror story into something multifaceted in meaning. A story lead entirely by women.

At first it is absurd that Utsuki would even entertain venturing deeper into this clearly disturbed mansion but as the plot progresses, with several clever twists, we come to learn that there is far more to her motives, which nicely subverts a classic horror trope entirely. She has a dual nature that allows Utsuki to walk the line of monstrous and helpless, defying the archetype typical of leading women in horror stories. Her battle is about stepping from the control of her father, who has kept his daughters isolated from society their whole lives. Doing so requires her to defy qualities she’s expected to have: Meekness and attractiveness. Utsuki undergoes a transformation which breaks her free of the mould she was raised into.

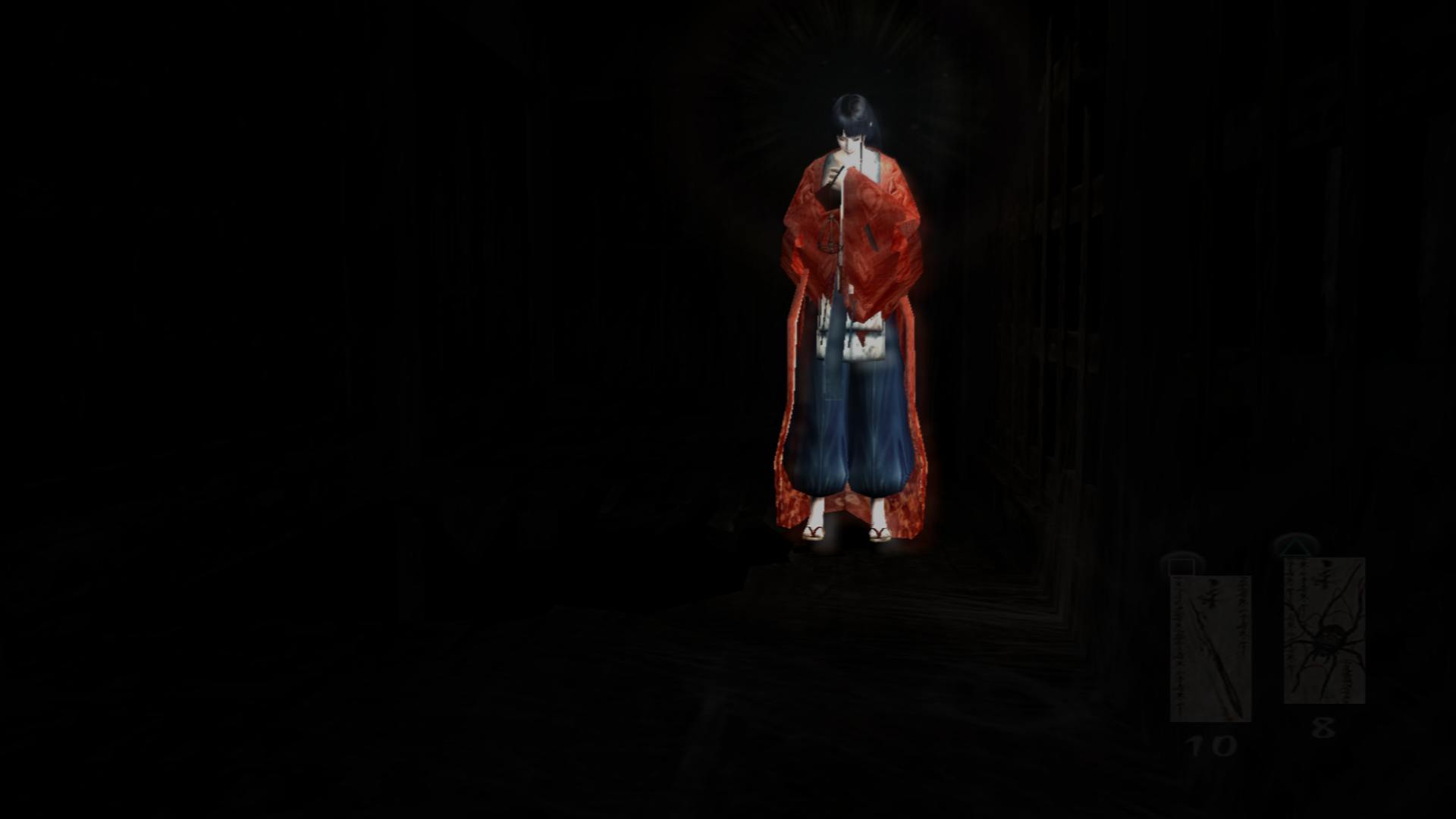

As you take Utsuki from helpless to capable, albeit in an unexpected way, her campaign ends and you begin again as Sakuya, an apprentice onmyōji who is far more capable from the outset, matching the player’s growing skill. Her outfit is more like the men around her, men who look down upon her, regarding her as out of place among their ranks. Even her personality and temperament represent where the player has come to: confident and eager to fix the tragedy unfolding around her. The characterisation extends to the characters weapons, though in a subversive way, with Utsuki wielding a knife that’s a poor weapon against the monsters but a hint towards her more dangerous nature. Meanwhile Sakuya wields a fan, a traditionally feminine symbol that is actually a more effective measure against monsters and spirits, embodying the qualities that allow her to emerge as the story’s heroine.

As their stories intertwine, it’s Sakuya’s kindness that sets her apart from everyone else in the narrative, hell bent on saving Utsuki instead of leaving her to her fate. It’s not hard to read the affection these two young women have towards each other as romantic. From the intensity of their first meeting to their being torn apart and drawn back together, their relationship hits many of the beats of a romantic subplot. Queerness becomes just another part of their defiance against the conservative society around them.

The third, unlockable character is perhaps the game’s most subversive. Abe no Seimei was a real historical figure and importantly, a man. Yet in Kuon, this legendary onmyōji is a woman. While Utsuki is suffocated by patriarchal authority and Sakuya must constantly assert her ability to work among her male peers, Seimei is powerful and transcends tradition. Her campaign literally stands apart from the established balance of Yin and Yang. She is beholden to nobody, allowing players to thwart male dominance and ego with a naginata (a sword spear typically wielded by women) and an unrivalled arsenal of magic,. As Seimei, the player is practically invincible and its closing moments are almost a fantasy, driving home the power and beauty that lies beyond tradition and gender norms. Meanwhile its villains, desperate to achieve immortality, only care to recycle the established order, even as it disrupts nature and rots the world inside out.

The game cautions against the very act of resurrection. Things have to come to an end, nothing can go on forever. It’s a recurrent theme in the studio’s work, especially in the Dark Souls series. So perhaps Kuon is never meant to return. But it showcases such a strength in horror and contains a story that is as fascinating now as it was then, that it would be a shame if From Software never returned to Kuon or the survival horror genre. Especially since tracking down a physical copy is an ordeal, with the game never officially re-released.

If you can get your hands on it then I’d honestly say time has been good to Kuon and what dated it then now highlights the things that are timeless and powerful about it. With a wave of indie horror digging into retro styles, Kuon feels in tune with modern sensibilities but even still, and it saddens me to say so, there really is nothing quite like it.